Print  |

|

Being a linguist

Posted by Colette Grinevald et James Costa on October 7, 2011

By Colette Grinevald, linguist, DDL laboratory (Language Dynamics), University of Lyon 2, and James Costa, Research associate, French Institute for Education, Ecole Nationale Supérieure, Lyon, France.

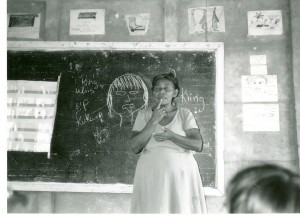

Miss Nora teaching rama – © Colette Grinevald

Emergence of a research discipline

The phenomenon of language extinction has been known for numerous decades, but an active form of awareness rose in the 1970s in various countries such as France, UK, and USA.

Not until the dawn of the 1990s, however, did the theme of endangered languages truly emerge. The period was marked with the 500th anniversary of the Discovery of America (1492-1992), celebrated by some, criticized by others. It was then that the work of several researchers encountered the demands of field activists in indigenous communities of the Americas. This encounter created a shockwave among linguists, and showed to be the actual kick-off of a new field of research.

From then on, a network of linguists from America, Australia, and Europe was put in motion – linguists who shared a long experience in the field upon various contexts of language endangerment. They began to coordinate their projects, organize conferences everywhere across the planet, and produce a number of individual or collective publications.

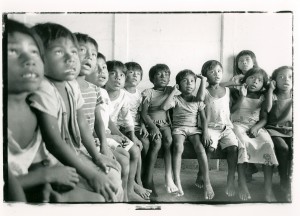

Children learning Rama – © Claudia Gordillo

The part played by linguists

Linguists involved in this new span of research soon considered it was in the interest of their own profession, as well as their responsibility as citizens of the world, to sound the alarm on the severe precariousness of most of the world’s languages.

Beyond the research activities they have been trained for, rises the question of their role in respect to the demands of populations: while their academic work consists in describing and documenting these languages – which remain relatively or completely unknown so far, and usually also un-written –, what the populations ask for has more to do with the revitalization and revaluation of their endangered languages.

Faced with the issue, a common attitude, dominant in an ideological context in favor of monolingualism, consists in doing nothing, and considering processes of language extinction as a natural outcome of processes that were always at work.

Another attitude admits that linguistic phenomena aren’t natural, quite the contrary: they are cultural, deeply ideological, and often involve unbalanced power relationships.

Thus developed, in the course of the past twenty years, a discourse aiming to display arguments in favor of maintaining as much linguistic diversity as possible, as a constituent of the human specie.

oung women playing in Rama- © Colette Grinevald

Summing up the issues at stake

In 2000 British linguist David Crystal published a prime example of a case statement on endangered languages. According to Crystal, linguistic diversity must be secured for the following reasons:

- We need diversity

This argument is based on themes developed in anthropology since the beginning of the 20th century, particularly in France with Claude Lévi-Strauss. The idea behind this argument is that diversity (be it biological, cultural, etc.) is the foundation of life on Earth. We, therefore, refers to humanity as a whole.

- Language expresses identity

This statement is based on the traditional people/language associations implied by Nation State ideology, claiming that one cannot be Spanish, French, Welsh or Rama without speaking Spanish, French, Welsh or Rama. Together with the extinction of a language, therefore, national or cultural communities also give up a significant part of themselves.

- Language reflects the history of populations

On one side, the scientific study of a language’s vocabulary often plays a part in retracing the geographic origin of the population who speaks it. On the other, a population’s language allows its oral literature and specific concepts to be handed down before being lost though possible translations or transmission to a third language.

- Languages contribute to the global knowledge of humanity

Each language embeds a key-fraction of humanity’s global knowledge, the loss of which might affect the construction as a whole.

- Languages are interesting for themselves

This argument, peculiar to linguists especially, consists in asserting that languages themselves are human and social constructions that are worthy of interest, and that their study is a way to comprehend human potential. From a linguist’s standpoint, letting most of the world’s languages disappear would be accepting the loss of the discipline’s essential working material. In that sense, according to some, languages are jeopardized masterpieces just as are certain historic monuments.

In conclusion

Endangered language issues, alongside language issues in general, are profoundly ideological issues – power issues. Engaging in favor of one perspective or another, beyond their scientific work on these languages, linguists are necessarily drawn to address the ideologies underlying their acts and their very conception of language and speech.

NB: For further insight, refer to the collective work “Linguistique de terrain sur les langues en danger” [Field Linguistics on Endangered Languages] directed by Colette Grinevald and Michel Bert – ‘Faits de langues’ collection (Ophrys).

Order online here.