Print  |

|

Chukchi

Page created by Charles Weinstein, professor – “agrégé” – and author of Parlons Tchouktche (“Let’s speak Chukchi”).

Data on Chukchi

Alternative names: Tchouktche, lygorawetlat.

Chukchi is the name given by the Russian and adopted at national level. The indigenous population refers to itself using the name Lygorawetlat.

Classification: Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages

Main dialects: There are no Chukchi dialectal variants per se, but clear differences between the traditional activities of reindeer farmers on one side and marine mammal hunters on the other account for the existence of specific vocabulary.

The expanse of the Chukchi territory has also generated differences in the meaning of words. Different terms can refer to one and the same object. Some words can have their own variants. And the speech of men is different to that of women.

For the speakers, however, whether they’re from the tundra or the coast, the language bears a great unity and presents no significant obstacles for understanding. The unity of the language owes to age-long contact between the people from the tundra and those from the coast. It also owes to the spiritual culture of the Chukchi. Human beings are part of a whole, without considering themselves the center of the universe. They’re in constant communion with nature and the forces of nature. Spirits are omnipresent. Each place has its own spirit, which one should respect and honor. Offerings should be made, even minor. But one must also beware of malicious spirits, who try to harm the humans.

Area:

1. Chukotka. 2. Northeastern Yakutia. 3. North Kamchatka. The first populations – Yupik (Eskimo) (about 1,500 people) and Lygorawetlat (Chukchi) (about 15,000 people) – became a minority during the second half of the 20th century. It is a closed area: any visit to and beyond the capital, Anadyr, requires a special authorization from local authorities. Which obviously does not make research activities any easier.

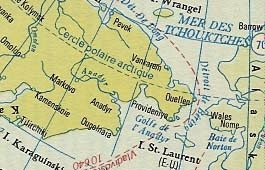

Chukotka is a peninsula of over 700,000 km2 located on the northeast end of Eurasia. It is bathed with the Arctic and Pacific oceans, and separated from Alaska by the Bering Strait. In some parts the northeastern Chukchi massif reaches 2,000 to 2,200 meters. Winters are harsh, and the inland climate is also tough. Archeological research has revealed that the Chukchi have been living there for millennia.

Map of Chukotka © Charles Weinstein

Number of speakers:

7,742, according to a census led by the Russian federation (2002). These figures (the only ones available) must be put in balance. The number of native speakers is probably lower (see Vitality and Transmission).

Language status: No official status.

Vitality & Transmission:

Chukchi is considered “severely endangered” by UNESCO.

Nowadays the ethnic group, its culture, and language are faced with serious threats. The number of speakers is difficult to assess. There is no official status of Chukchi language. The teaching of the language lacks both quantity and quality. And – with some exceptions – it is no longer spoken but by people over a certain age. Chukchi is given up for Russian.

The Chukchi still spoke their language until the 1950s. In less than half a century the Chukchi language underwent an unyielding decline. In a preface to In the steps of Bogoraz (see bibliography), the researcher I. Krupnik observes: “The end of the 20th century has been a cultural disaster for the people of Chukotka…” Same compendium, page 130, V. Zadorine writes: “Peoples of the Russian Far North have lost everything they had achieved along the centuries in a brief period of time, including their historical memory and traditional knowledge“.

On the language, a Chukchi woman, G. Tegret notes in 1995: “There is a process at work (explainable through history, which is no consolation), that of the decrease of the usage-span of Chukchi language, the reduction of its active vocabulary, and the number of people who bear the language.”

In a letter sent on January 25, 2004 by the famous Chukchi writer Youri Rytkhéou to the author of this very sheet and his wife, the writer points out, bitterly: “Yes, my mother tongue is in a tragic, disastrous state. It is threatened with extinction… There are very few genuine holders of the language left…“

Historical & ethnographic details

According to author, ethnographer, and linguist W. Bogoraz, exiled in the Kolyma region in 1890, the Russian Cossack from eastern Siberia recall the Spanish conquistadores in many ways. He mentions “their indomitable bravery and brutal greed… They treat the indigenous people without the slightest sense of pity” (Bogoraz 1904-1909). They refused to pay their tax in kind, convert to the Orthodox Church, or adopt Russian names. The resistance of the Chukchi, who were committed to the idea of fair barter but opposed to that of a one-way tax, revealed a proud and assertive people to the Russian. The imperial ukase of August 10, 1731 recommended ending the war raised against them.

W. Bogoraz further writes: “The first thing brought by the Russians was a request for tribute and war… They (the Chukchee) successfully repelled the first and held their ground in the second; and when the war at least ceased, they preserved intact all their national vigor… The Russianization of the Chukchee has made no progress at all during the two centuries of Russian intercourse with the Chukchee. The Chukchee kept their language, all their ways of living, and their religion…” (W. Bogoraz 1904-1909: 732).

State, formal law, and common places of worship have never been part of the Chukchi community. The rules of society are handed down orally. Children are taught how to live in the harshest natural conditions, endless tundra on one side with its dangerous blizzards, ice-cold ocean on the other with its violent storms.

After 1917 the new Soviet authorities gradually established their “cultural bases”, reaching over the political, social, economic, cultural, and medical spheres. The aim was to justify the validity of the measures ruled by the authorities, draw people towards social organizations, convince parents to attend literacy courses and send their children to school, convince women to resort to doctors, etc. The teaching of literacy was well accepted, but the children were placed in boarding schools, far away from their parents living as nomads with the reindeers. Over time they lost contact with their language, culture, and traditional knowledge. Latin character-based alphabets were created for local languages in 1930.

After 1990, the influence of indigenous people on the political and social life remains close to non-existent. The 1990s account for a steady deterioration of the economic fabric. Reindeer farming collapsed as the State completely withdrew. The health situation deteriorated. The return of tuberculosis and other diseases has been mentioned. Medical care was suddenly charged.

Looking for traces of a political life there would be in vain. There is no racism, officially, but the locals suffer discrimination de facto. In other circumstances one might have asked why they do not have their own associations, unions, political organizations. But there is no actual tradition of association here, adding to the sheer lack of basic material means. And any will for struggle is discouraged at the highest levels. The Small Ethnicities Association is one of the wheels of administration; it would not be able to look out for the people’s interest even if it wanted to. In fact, it essentially exists on paper, hence the people’s lack of interest in the organization.

Bibliography

Waldemar Bogoras (Wladimir Bogoraz). 1904-1909. The Chukchee. Leiden-New York.

P. Skorik. 1961. Grammar of the Chukchi Language. Book I. The U.S.S.R. Academy of Science. Moscow-Leningrad.

P. Skorik. 1977. Grammar of the Chukchi Language. Book II. Naouka. Leningrad.

Galina Tegret. 1995. The Chukchi, traditional vocabulary of the tundra and coasts of the Providenia district. Regional Institute for Advanced Teacher Training. Anadyr.

Tропою Богораза. 2008. In the steps of Bogoraz (compendium in Russian). Moscow.

Charles Weinstein. 2010. Parlons tchouktche. L’Harmattan, Paris.

Charles Weinstein. 2010. Récits et nouvelles du Grand Nord. Translated from Chukchi into French by Charles Weinstein. L’Harmattan, Paris.

Links

Charles Weinstein’s website on Chukchi language and literature

Please do not hesitate to contact us should you have more information on this language: contact@sorosoro.org