Print  |

|

Vanuatu: a fragile diversity

Posted by Alexandre François on June 14, 2011

Dr Alexandre François, LACITO-CNRS, Australian National University

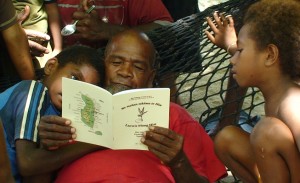

Alexandre François and †Maten Womal, one of the last speakers of the Olrat Language.

Last week, Alexandre François presented an overview of multilingual practices in Vanuatu, the country with the world’s highest linguistic diversity. He described how the traditional lifestyle of Vanuatu, with its decentralized organization and the absence of pressure towards uniformity, enabled languages with no more than a few hundred speakers to thrive and keep being handed down over the centuries.

Today he explains how linguistic diversity, despite being still very present in modern Vanuatu, is becoming ever more vulnerable.

Historical upheavals

The archipelago of Vanuatu went through a period of disruption towards the end of the 19th century.

The first contacts with European sailors triggered dramatic epidemics.

In addition, almost at the same time, the islands of Melanesia were losing their population because of Blackbirding – that is, the massive recruitment of workforce for the plantations of Queensland and Fiji. Missionaries at the time reported how, within only a few years time, they witnessed the demographic collapse of numerous villages that were once thriving.

In the northern area of Vanuatu I’m working on (the Banks and Torres islands), the linguistic density is still amazing today, with ten little islands counting as many as 16 different languages. However, the oral tradition as well as historical documents reveal that the same area, around 1860, was home to 35 distinct languages! This says a lot about the collapse of linguistic diversity within only a few decades…

The last witnesses

Even though the current times are less troubled, we are still observing indirect consequences of that demographic crisis. At the turn of the 20th century, many families from the highlands left their depopulated hamlets and resigned themselves to move down to the coastal villages, where the new Christian churches had been installed. Blending into the population of larger villages, these families were inevitably bound to replace their own language with that of the majority. Children born after this period, in the 1930s and 40s, were the last to ever hear the ancestral languages spoken by their parents; these individuals, now in their 70s or 80s, are the last speakers of languages which are almost extinct.

In the course of my research I always did everything I could to encounter these last witnesses of an ancient diversity, and record their languages while it was still possible. This is how I worked on Araki – the language from which the name Sorosoro was borrowed – but also on Volow, Lemerig, Olrat, Mwesen, Lovono, Tanema… The speakers of each one of these languages can be counted on the fingers of one hand. This reminds us that the linguistic diversity of our planet is a fragile flower.

The importance of transmission

Fortunately, the languages of Vanuatu aren’t all threatened to the same extent. For many of them, predictions on the mid-term are even optimistic, for multilingualism is in fact still very alive in the rural areas of the archipelago. The key lies in the transmission across generations: a language can last even if it is only spoken by two hundred people, providing the parents speak it to their children.

Most of the languages in Vanuatu are currently in this situation. The continuity of their transmission to the younger generations protects them, at least for now, from the risks of extinction. Yet their low demography remains their soft spot: an increase in migrations to cities, or a sudden cultural modernization, could be enough to trigger similar upheavals to those of the past century.

How linguists can help

Linguists do not hold all the keys to guarantee the survival of a language: this mainly depends on the speakers’ will to hand down their knowledge to the following generations. However, we can do our part to have these languages live on – in two different ways.

First, the task of language description and documentation, which takes the form of grammars, dictionaries or academic articles, is essential to preserve the human linguistic heritage. This is also true for those languages whose fate is already sealed: even though we cannot get them back afloat, at least we can rescue their treasures while it is still time. Take Araki, which was spoken by around fifteen people in 1997, by only five or six nowadays: there is little hope it can ever come back to being the thriving language of a whole community. But at least the grammar, dictionary and collection of stories I have produced will contribute to safeguard the memory of this unique language. The last speakers and their families are grateful for all this work – be it merely of a symbolic nature.

Perspectives are different with languages that are still healthy. The work of linguists can serve the community, in turn, by strengthening patterns of intergenerational transmission. This effort may take various forms, for instance by contributing to the introduction of vernaculars in the education system. I’ve just returned from a stay in Vanuatu last month, where I encouraged teachers of primary schools to include in their curriculum not only French and English – as is the case today – but also the mother tongues of their students. Interestingly, the government of Vanuatu is precisely shifting its new language policy into the same direction. To play my own part in this great project, I visited schools and gave classes to children aged 5 to 13; I showed them the literacy books I had just produced so as to teach the orthography of the vernaculars. I saw their eyes gleam with awe when they realized that their language, too, could be written.

Reading an Alphabet primer. © A. François

For further insight:

Alexandre François’ personal website: http://alex.francois.free.fr/