Print  |

|

African plurilingualism in writing

Posted by Aïssatou Mbodj on February 6, 2011

AïssatouMbodj is a postdoctoral researcher at the Zentrum Moderner Orient (Berlin) and research associate at the EHESS-based Centre d’Etudes Africaines.

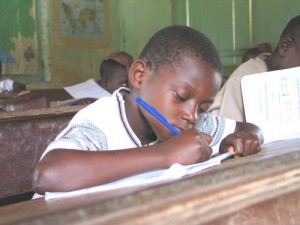

BY Bruno Ben Moubamba (CC)

Contemporary African societies being plurilingual, regardless how well this is taken into account in linguistic policies, is obvious nowadays. While undisputable for spoken language, how much of this applies to writing?

The main written languages in Africa are the official languages – the old colonial languages – as well as Arabic, the language of culture and religion overlarge patches of West and East Africa.

It is worth noting that this does not include countries or areas with both a presence of orally fluent and anciently written African languages: the languages of Ethiopia and Swahili, in East Africa.

Outside these cases, however, a disjunction between oral and written languages remains the most common situation: the number of oral languages in Sub-Saharan Africa is significant, yet very few of them are used in writing.

Considering the cases of French-speaking countries where French is the only official language, it appears that African languagesrecognized as « national languages » are doing rather fine oral-wise: revealing examples are linguasfranca developing at country scale such as Wolof in Senegal, or Bambara in Mali.

But these languagesstruggle in achieving the status of written languages. True, since the 1960s, efforts have been granted to consolidate these languages through the adoption of an official spelling system and development of grammatical vocabulary. However, their written use remains confined to very limited fields and social spaces, like adult literacy teaching in rural areas.

That being said, in some places, efforts are also made to develop bilingual schooling: this is the case of Mali where following decades of experimenting bilingualism at school, it has now stepped into a phase of general implementation. The most important now is to make sure this willingness maintains itself over time, and observe whether this bilingual schooling is enough to make these languages enter the use of daily writing.

But it is important not to generalize at continent-scale, because African languages have very diverse relations towards writing. For some, the transition to writing and print reaches back to the colonial or missionary periods when literatures were born:Yoruba in Nigeria,or Kinyarwanda in Rwanda. On the other hand, many languages are exclusively oral and remainundescribed. Others have been codified but their written form lacks use by the speakers themselves.

Which leaves the question of the choiceof script: there are other spelling systems than the Latin system used by a great number of languages; some writing traditions in Africa turn to different kind of scripts. Ajami, which consists in using Arabic script for languages other than Arabic, is a common practice, for example in Hausa (spoken in Nigeria, Niger, and West African countries). In other places can be observed the use of an original script, sometimes with great vitality on regional scale,like the N’Ko writing system for Manding languages in Guinea and Mali.

While on the whole African languages remain underdeveloped in writing, there is potential to reinforce their use: our era has given birth to new writing practices, often very different to the bookish forms to which the idea of script is generally associated.

Thus the walls and signs of African cities display inscriptions bearing the blends of form, language and script way beyond the authorized uses of the official language.

Also worth pointing out, the use of so-far underwrittenlanguages when it comes to new technologies of information and communication, especially texting, emails and newsgroups. These new practices force to reconsider the disjunction between oral and written langue, and heralds a bright future for some of the many African languages, both orally and in writing.