Print  |

|

Multilingualism in Pakistan

Posted by Matthias Weinreich on April 8, 2011

By Matthias Weinreich who has been working for many years as a linguist in Northern Pakistan with a special focus on Dardic languages and Pashto; author of “Language Shift in Northern Pakistan. The Case of Domaakí and Pashto“.

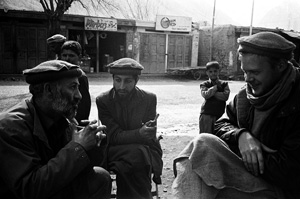

Northern Pakistan, 2003 – Photo: bogavanterojo (cc)

But the people in Pakistan, they all speak Urdu, don’t they?

Yes, most of them certainly do. And this is not surprising, since all over the country Urdu is used as medium of instruction in primary education and as language of interethnic communication. In addition to this, Urdu in Pakistan also enjoys an extraordinary high official prestige: It is one of the two languages explicitly mentioned in the 1973 constitution (the other one is English, spoken mostly by the urban elite) and it serves as a key symbol of the country´s national unity.

However, one should not lose out of sight that Urdu is and has always been the mother tongue of only a minority (presently about 8 %) of the population of Pakistan. The rest of the people (more than 150 million) speak other languages as their mother tongues.

So, how many different languages are there spoken in the country?

This is difficult to say, as a precise answer would, of course, be linked to the not always easy task of differentiating between a language and a dialect. For example, depending on the criteria applied, Pothohari, Siraiki and Hindko, all of them members of the Punjabi-related dialectal continuum prevalent in western and central Pakistan, can be regarded as varieties of one vernacular (Punjabi), or as three independent languages.

In any case, a conservative estimate would be that there are not less than 60 languages spoken as mother tongues in Pakistan. Reflecting the region´s long and eventful history, these idioms represent a variety of language families and branches, mostly of Indo-Aryan and Iranian extraction. But they also include representatives of Dravidian (Brahui, in central Balochistan), Sino-Tibetan (Balti, in the east of Gilgit-Baltistan) and even one language isolate (Burushaski, in the northern valleys of Nager, Hunza and Yasin).

The number of speakers of each language varies from more than 50 million people in the case of Punjabi to less than 250 souls for Aer (Sindh) and Gowro (Gilgit-Baltistan).

Matthias Weinreich in Pakistan – Photo : Silvia Delogu

Are some of those languages seriously endangered ?

In Northern Pakistan alone there are no less than four languages which are threatened by extinction: Gowro, Badeshi, Ushojo and Domaakí.

Socio-linguistic data from the region is scarce, but at least in case of Domaakí (the language of the Dóoma, traditional blacksmiths and musicians in Gilgit-Baltistan), general multilingualism among its few remaining speakers (less than 250 people, mostly elderly) is accompanied by a strongly negative language attitude, a truly inauspicious combination which makes it rather probable that in one to two generations the Dóoma´s original mother tongue will cease to exist as a living language.

Besides Urdu, are there any other languages of interethnic communication?

Yes, there are, and quite a number of them. While Urdu is spoken and written throughout the country, each of Pakistan’s federal provinces is characterized by its own distinctive majority language:

– In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pashto is used as lingua franca on all its territory except in the north, where this function is fulfilled by Dardic Chitrali.

– Punjabi is the language of Punjab, with its variety Hindko used as lingua franca at the northern border with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and its south(weste)rn varieties Multani and Siraiki on the territory close to Sindh and Balochistan.

– Sindhi is majority language and provincial lingua franca in most of Sindh, but in the southern megalopolis of Karachi it retreats before Urdu and in the north of the province it gradually gives way to Siraiki.

– In Balochistan most people speak Balochi, except alongside its frontier with Afghanistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where the main medium of interethnic communication is Pashto.

As one would expect, it is in the zones where two or more regional communication languages overlap that multilingualism is most prevalent. For example, Siraiki and Sindhi mother tongue speakers living on both sides of the Sindh/Punjab administrative divide will often be fluent in each other´s languages. While Pashto speakers resident in Hazara District (south eastern corner of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) will usually know Hindko and many Hindkowals from the same region will also be conversant in Pashto.

So many regional languages! Does this mean that everybody in Pakistan is at least bilingual?

In a way it does, but one has to consider different degrees of fluency. Learning to speak a new language is normally motivated by practical considerations. Therefore, Pakistani men who work outside the house are more likely to master the regional lingua franca than women who are expected to stay at home. Or a bazaar trader might speak several languages on a level allowing him to conduct business with his customers, but might not be able to use these idioms in any other situation. Especially for speakers of small minority languages (i.e. languages other than Urdu, Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi and Balochi) multilingualism is strongly linked to domain.

For example: Mother tongue speakers of the already mentioned Domaakí, men and women alike, are normally also fluent in Burushaski and/or Shina, the idioms of their host communities. Besides this, all Dóoma men and some Dóoma women speak (and even write, if they have attained school) Urdu, which is the area´s main lingua franca. This means that Domaakí is normally used at home, Burushaski/Shina in the village and Urdu with strangers and for written communication.

The quoted example demonstrates that for representatives of minority language groups (approximately 5 % of Pakistan´s population) it is nothing special to be conversant in three-four languages. Most other individuals in Pakistan will know at least two.

◊

See Matthias Weinreich’s book: Pashtun Migrants in the Northern Areas of Pakistan